“Immunocompromised” is a fancy way of saying that, for a variety of possible reasons, a person’s immune system doesn’t function as the gatekeeper of the body like it should. Basically, you ain’t got no shields on this spaceship.

I’ve written many times about how and why my immune system doesn’t do its job. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, I’ve learned how many people around me are in the same boat. We’ve got ‘vulnerability status.’ The only good thing about that is priority grocery delivery.

My illness, Ankylosing Spondylitis, causes my immune system to attack healthy tissue, meaning inflammation and pain. Like many autoimmune disorders – Crohn’s Disease, Multiple Sclerosis, Lupus – any number of things can send my system into a ‘flare.’ This is the ‘leaf-detecting burglar alarm’ metaphor I’ve used before. Most people’s burglar systems only sound the alarm when the house is broken into. Mine can get set off by a stray leaf blowing past.

People can also become immunocompromised from past or present cancer, HIV, treatments and medications (ironically), age, diet, drinking, and smoking.

The steamroller ‘solution’ to an over-reactive immune system is ctl+alt+delete. Immunosuppressant medications are a blunt instrument with a mixed success rate. They also, obviously, do something dangerous: suppress our body’s normal reaction to a threat. Whether that threat is real or just a leaf is of no importance. A strong enough immunosuppressant doing it’s job will stop your burglar alarm – meaning anyone can just wander in.

Obviously, right now, the threat is real, which is why people with compromised immune systems are being encouraged to take extra precautions. It’s easier for us to get sick, and when we do, it’s easier for us to get really, really sick.

Old news: I got diagnosed with AS in 2014. Before the diagnosis I was treated in hospital with my very first immunosuppressant: Prednisone. Pred is both a miracle drug and a nightmare. High doses are usually used in very short periods. It gave me manic energy, euphoria, and pain relief. For another person with AS, it caused multiple organ failure. The side effects long-term are terrible, and so is the withdrawal – it took close to two years to reduce my dose from 20mg to 1mg, by 1/4 of a milligram at a time.

Again, old news, but access to stronger immunosuppressants in New Zealand requires a Special Authority approval from PHARMAC, due to the risks and expense involved. To get that, I required an MRI showing the inflammation and damage in my spine. I will never forget the people who contributed to getting me that proof as quickly as possible. The kindness was overwhelming.

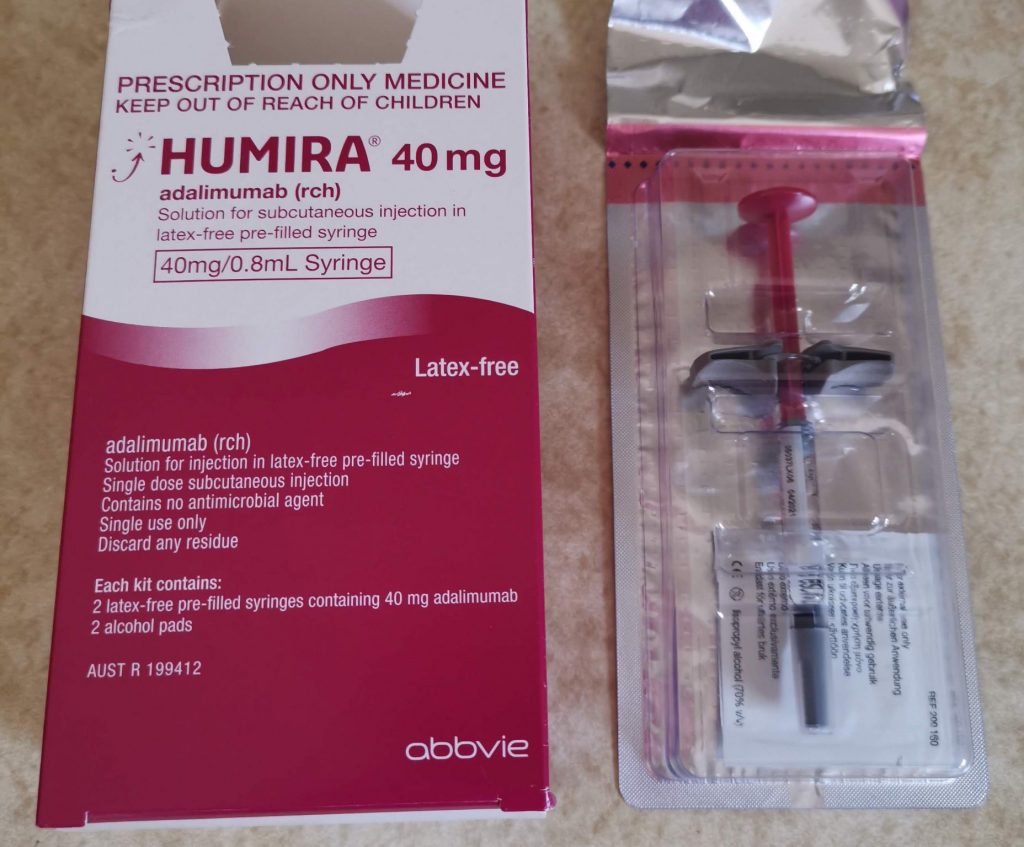

Having got the ‘sick enough tick’, I was prescribed Humira, a TNF inhibitor in the form of a fortnightly self-administered injection. TNF stands for Tumour Necrosis Factor-Alpha, a natural inflammatory substance which many people with autoimmune disorders have too much of. TNFIs block it, weakening your immune system and slowing or stopping inflammation.

Humira syringe for self-administration

At this point my disease was completely uncontrolled and I was begging for relief. Devastatingly, the Humira didn’t work. Neither did Enbrel, also a TNFI injection, Methotrexate, a chemotherapy pill, or, eventually, the biggest shotgun on offer: Infliximab infusions.

In 2017, I was going to hospital for Infliximab (initially designed as a cancer drug) every 6-8 weeks. The infusion took several hours, a necessary slow drain because it can cause anaphylactic shock, heart failure, seizures and many other fun things, so you’re monitored extremely closely.

Luckily I did not experience any serous response. The only discernible results from the cocktail of drugs were intense fatigue, nausea and vomiting, hair loss and weight gain. I stopped. There were no further ‘treatment’ options for the illness, only ones to help manage the symptoms.

Over the last three years I’ve found some things that help, and I’ve been ever-so-slowly getting better. But then, a nurse mentioned to me that sometimes, TNFI’s work better the second time around. I consulted my rheumatologist and decided, literally, to give Humira another shot.

- Side A

- Side B

This is the list of warnings and side effects that come with it. A double-sided table cloth. By the time Nik finished reading it I’d already done the first injection. Not because I felt casual about it – anything but – but because I’d been here before. I didn’t need to stop at the *danger danger* signs to remind myself what they meant.

The first time around, I used an automated pen to administer the shot, but that’s quite difficult to get right, and Humira costs somewhere around the $2k mark. Per injection. It’s not something you want to fuck up, even if you’re not paying the bill (thank you, subsidised healthcare).

So I switched to a pre-filled syringe. I use an ice pack to numb my stomach as much as possible. Because I’m small, and because I scar easily (as shown by my navel piercing from 17 years ago), it can be difficult to find enough unscarred fat to inject into. The needle doesn’t hurt, but the drug going into the muscle sure does.

- Above: Syringe and instructions. Left: Pinhole bruises, very faint redness of swelling and scars underneath.

The shots take 6-8 weeks to start working. I am at Week 8. And I am very excited because (touch wood) I think it’s actually doing it’s thing for me this time. I have slightly more energy, slightly less pain. Discernible enough to give me hope.

I am also, of course, the definition of ‘immunocompromised in a pandemic,’ so if I come into contact with COVID-19, I have no idea how my body would react. I know I’m not alone in this. Today, wearing a mask and circling widely around others in the supermarket in Nelson, I felt a little silly. Paranoid, maybe. But I’d kinda rather be paranoid than, y’know. More sick.

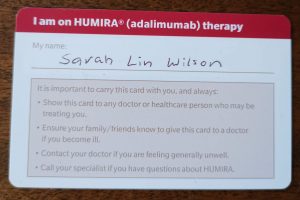

I also get to carry round this nifty card which lets people know why I might feel that way. It has the doctor’s details and other important info on the back.

It’s kinda weird to be injecting yourself with something that could kill you, so that other things don’t kill you, but some of those things could because of the thing you’re injecting yourself with?

But I can tell it’s working. The last couple days before the dose is due, my energy drains away, my pain creeps back up. Which means on my good days, I’m doing more than I thought possible after my diagnosis. So I’m going to keep going, because getting my life back is, actually, worth the risk of anything happening to it.