My sex ed at school was rudimentary at best and focused very much on the many ways in which you could get pregnant and/or STIs and/or die. Not exactly the most helpful education I’ve ever received.

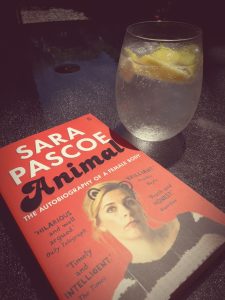

Earlier this year I read Sara Pascoe’s Animal: Autobiography of a Female Body, and I swear I learned more from that one book that I’d learned in all my 31 years of occupying this body combined. And that’s ridiculous.

Sex ed at my all-girls high school involved two memorable classes. In the first, we were taught how to put condoms on vaguely penis-shaped cylinders of wood, mounted upright on a sturdy base. Most of us missed the lesson in all the embarrassed laughter. One girl asked to wait outside. Another fainted.

To be fair to her, in my memory those jolly wooden dildos were alarmingly large, which is either a result of me never having seen an actual penis at that point and so therefore no basis for comparison, and/or was a deliberate choice intended to frighten us away from heterosexual sex. Two girls in my year had babies so I’m not sure how effective it was.

The second class was, I think, a science one, rather than health, which is interesting. I remember sitting in the science lab watching the most horrifying video I had ever seen in my young life: a montage of naked women, complete with 80s bush, screaming their way through bloody childbirth.

Well, if anything was going to ensure our abstinence, it was going to be that. I never wanted to go near a wooden penis again.

All jokes aside, it’s become very clear to me that the rudimentary education I received in school focused very much on protection from STIs and unwanted pregnancy, and while that’s important, there were some vital parts that were left out of the conversation.

The most obvious one is consent, but that’s a post on it’s own. What I want to focus on is women’s knowledge of their own bodies, especially with regard to our vaginas and reproductive organs, hormones and cycles, and fertility.

I can’t remember whether I’ve already admitted this publicly or not, because it’s not something I’m in a hurry to own up to, but a couple of years ago (so I would have been maybe 29), I snuck out of my friend’s house in Wellington and made a very expensive trip to the after hours clinic. Why?

Because I thought I had “lost” a tampon inside my vagina.

Thinking about it now, I’m cringing and laughing and I’m also really, really angry. Because while you can never rule anything out completely – bodies are different and sometimes unlikely things happen – it is preeeetty much impossible that a tampon had somehow got sucked into the vortex of my never-opened cervix and was floating around in my uterus.

Now, having suffered through one failed and one difficult-but-ultimately-successful IUD insertion, I feel like I unequivocally understand that NOTHING IS GOING IN THROUGH MY CERVIX UNLESS I AM VERY MUCH TRYING TO MAKE THAT HAPPEN. Considering the level of pain involved in getting that tiny T of wire in there, I can see that it’s utterly hilarious that I thought an entire tampon was gonna slip on through without me noticing.

But I didn’t know that. At the time – at twenty-bloody-NINE – I didn’t know that. And while I’m really embarrassed about that, a quick google of “Can a tampon get lost in my vagina?’ tells me that many, many other women the world over also do not know how their bodies look.

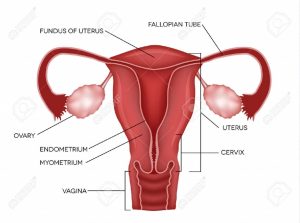

Sure, we’ve all seen the happy little diagram that makes your uterus look a bit like a goat’s head, with the fallopian tubes and ovaries being tiny horns. But that leaves so, so much out of the equation.

Until I asked the gynaecologist to take a photo (I think I must have been delirious by this point), I had never seen my cervix. I stared at it later, zooming in, closing one eye, but I was still like “Huh?” This thing that I’ve been carrying around inside my body for 31 years looked nothing like I imagined it would. And unless you’ve had children, you probably don’t know what yours looks like either.

I think that that sort of information – teaching women what their reproductive systems actually look like, is one of the most basic steps to understanding our bodies and exercising bodily autonomy.

We also need to know more about hormones. Until I read Animal, the only hormones I’d ever heard talked about were testosterone, which belonged exclusively to men, and estrogen and progesterone, which belonged exclusively to women. Because these hormones are usually only spoken about in relation to sex or reproductive cycles, I had this weird idea and that’s where they existed in the body.

So, newsflash for me: There are loads of different kinds of hormones, hormones are chemical messengers that are all created in the brain. Your uterus does not make estrogen. Estrogen comes from your brain to tell your uterus what to do. This is very basic and inexact science, I’m sorry, but I hope the point is obvious.

A few months ago, I went to see the doctor because I wanted to get my hormone levels tested. These levels fluctuate all the time, but mine are impacted by my illness and the medication I’m on. I was keen to get some stats, because I’m into that sort of thing, and I wanted to get a measure now so I can see what’s abnormal, and have something to compare to in a few months when I’m hopefully on less meds.

The doctor wanted to know why I would bother getting this information. He asked if I was trying to get pregnant. He asked what contraception I was using. I was baffled by this interrogation. The doctor tried to dismiss me.

“Hormones don’t effect anything,” he said.

I was flabbergasted. What on earth could he mean? Hormones effect So Many Things, in everyone, not just women. I persisted, and eventually got the MedLab form for the tests.

Those tests came back abnormal, and provided really important information about my reproductive health.

If we as women are not taught in more depth about where hormones come from, reproductive cycles, and the impact this can all have, then we don’t have the tools to advocate for ourselves. And that’s very, very dangerous.

The proof of that is seen in things like what’s been dubbed “The Natural Cycles Disaster,” where a heavily-promoted ‘fertility app’ promised women it would tell them when it was safe to unprotected sex. The app, which claimed to be a 93% effective form of contraception, was cited by 37 women seeking abortions in Stockholm between September and December last year. It has been reported to Sweden’s Medical Products Agency for investigation.

The proof of that is seen in things like what’s been dubbed “The Natural Cycles Disaster,” where a heavily-promoted ‘fertility app’ promised women it would tell them when it was safe to unprotected sex. The app, which claimed to be a 93% effective form of contraception, was cited by 37 women seeking abortions in Stockholm between September and December last year. It has been reported to Sweden’s Medical Products Agency for investigation.

The creators and marketers of the app are absolutely at fault – but so is education. If women received better education about their bodies – and reproduction in general – they’d be less likely to believe that a temperature test could be relied on as contraception.

I’m not saying put away the wooden penises. But there has to be more to our learning than condoms and 20-year-old videos of childbirth. All women’s bodies are different, and there’s room to learn about all of them.

Education is power, and the act to not educate women about our bodies, or reproduction in general, has been a deliberate one. We can change that. We need to change that.

We can take the power back.

Another very good book, in which women do just that.