The Queer Art of Failing Better is Laurie Penny’s latest take on millennial culture, where she unpacks the good, the bad, the questionable and the queer in the Netflix show she calls an answer “for the capitalism-damaged and toxically masculine.”

Queer Eye is, at it’s most basic level, a show where gay men show straight men how to sort their shit out. Most of the time it’s feel-good, funny, and tooth-achingly sweet. But, as Penny eloquently describes, it’s also far more.

Labeling the rebooted series “a cultural intervention,” she explains the ways in which the show goes far beyond it’s predecessors, including how it’s teaching straight white men that their reign is over.

As Penny says, the Fab Five aren’t just here to show you how to style your beard or wear a French tuck. No, they’re here to point out to you, in charming, witty, and often gentle ways that you’ve been brought up to expect others to perform labour for you – cooking, cleaning, dressing, emotional support – and that time is over.

I watched Queer Eye obsessively, which means something because I don’t really watch TV. I’m a very cautious viewer because I get over-emotionally invested – so others who’ve seen the show won’t be surprised that I ended most episodes having a good old weep.

I love watching beautiful men tell mediocre men how to be better men. What can I say?

“This show isn’t about how to win at life, but how to fail with style. It’s about giving straight guys permission to be more gracious losers. It helps that the show doesn’t actually have winners. This is not the ruthless, dick-smacking, alpha-primate pursuit of victory-for-victory’s sake that provides a plot line for most American reality television as well as for American politics, presuming you can still see clear water between the two. No, this is an oddly compassionate exit interview for the middle-managerial caste of straight dudes who are no longer steering a culture that prizes their skill set above everyone else’s.”

There’s a lot of things about the show that are a feminist socialist dream. I think Laurie Penny puts it far better than I ever can, but there’s something else she does in that article that really interested me.

This is something that most of us are taught how to do in high school – and that’s present more than one side of an argument. Being able to research across sources, process and polish relevant info, and debate it out – oratorially or in an essay – is a great skillset, and one many of us are privileged to have.

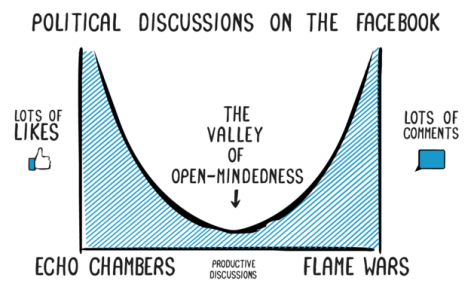

Over and over I see the words “echo chamber!” used with such pearl-clutching tones it makes me clench my teeth.

The people who are supposedly worried about my lack of personal development because I curate my online spaces so that I am not constantly confronted with viewpoints or material that traumatise me have missed a few crucial points.

- A complete and total echo chamber is not possible, unless one never consumes any media and lives in an airtight sarcophagaus. Therefore;

- I, the same as anyone else, am going to be exposed to opposing views whether I want to or not, in physical life and online

- I know what my limits are, and I feel no remorse about creating safe spaces for myself, as much as I am able

- People who yell about echo chambers are, generally: a) Privileged, in that it is ok and safe for them to expose themselves, at their leisure, to opinions and worldviews not like their own, and b) Not making any distinction between opinions and worldviews that are different, and opinions and worldviews that are opposing.

- I know this is a delicate distinction to make. But, for example, the worldview of a trans person is probably different to mine. I want to interact with them. I want to appreciate and learn. However, the worldview of a religious right-wing white supremacist whose belief system is predicated on me and people like me being less than human? Well. Quite simply, get fucked.

I think once you make that distinction, you can realise something very interesting. My echo chamber isn’t filled with my voice, bouncing off the walls. It’s filled with many diverse voices, saying important things, having interesting discussions, sharing vital information.

I don’t curate my online spaces because I love the sound of my own voice and don’t ever want to hear anything different or be told when I’m wrong, or because I feel like I’ve already learned enough and I’ve decided I’ll stop with the life lessons now, ta muchly.

I curate it because to do otherwise would cause me active harm. As I said in point 1, it’s not possible to curate your whole life. You’re going to sit on the bus behind someone who tells their friend that homosexuality is gross. You’re going to watch a movie that has an abusive character or a violent scene with no warning. You’re going to do something stupid like read a Stuff comments section where everyone hates beneficiaries. You’re going to have to live within systems that oppress you in more ways than people with privilege could ever understand.

That being the case, it becomes even more clear why curation is important.

I don’t want to only ever hear one side of an argument or one way of looking at things. I get my eyes opened all the time, and it’s great.

However. However. I do think we are losing something. And that something can generally only be found in long-form articles like Laurie Penny’s, in paid journalism where resource has been available to take time to think and research, in traditional formats like documentaries.

That thing is nuance. And it often doesn’t exist in spaces like Twitter and Facebook and in button-mash shareable bite-sized content and clickbait headlines.

When I first started reading Penny’s article, I was drawn in by her effortless writing and jokes and snappy commentary. She liked all the things I liked about Queer Eye, except she liked them better than I did because she’d actually thought about them more. By that I mean something like: she liked them with a deeper understanding. And I appreciated so much that she had articulated all of that for others, because one of the things that the Fab Five are doing is educate – not just educate the man they meet on each episode, but educate all of their viewers. And, as she says, it’s not all about the queerness. The show isn’t just a channel for a message of tolerance; that’s absolutely base level. It’s way beyond that, this is 20gay-teen, if you’re not on board you better find a lifeboat because you’re getting left behind.

But, I wondered as I worked my way through the article, was she going to address some of the reasons many members of the liberal community didn’t like the show? And especially, was she going to address that episode, with the Trump-supporting cop?

And she did, to the best of her ability. I don’t think any of us could truly understand what that episode might have felt like for black people, especially black gay Americans. But she didn’t sweep in under the rug for the sake of a pretty narrative. Her criticism of the show was given as much weight as her praise of it, and all of her arguments came together in a way that proves you can present a nuanced view of something. It’s just that it’s much harder to do in an economy that’s hungry for anger, for No-Shades-Of-Grey, for headlines that tell a whole story.

I often think of that when I want to write about something, and I wonder how much value it has if it’s more thought than yelled conclusion, more question than clickable content.

That’s a dangerous position to be in – determining something’s worth by its popularity – especially if that thing is part of your identity. It’s not a new proposition, but the “free market” shouldn’t be ultimately responsible for the proliferation of certain ideas.

Now that really would be an echo chamber.