I have OCD. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. And, bizarrely, it’s one of the few mental health disorders that have been so normalized by current society that, when you tell people you have it, they laugh.

When I tell people I have OCD, they picture the things popular culture has told them are OCD traits or behaviours. Hand washing, flicking lights on and off, only stepping on certain paving stones. To the outsider, those things might seem funny, or at the very least just a minor inconvenience.

They might also think you mean that you’re “just a neat freak” or like to have things a certain way.

For some people, that is how their OCD presents: with repetitive or checking behaviours; with cleanliness and organisation.

But there’s nothing minor or funny about these things, no matter how many times you might have laughed at Monica on Friends playing this exact part.

My friends used to joke that I was Monica, and I took it in my stride. They were right, if I were to be anyone on Friends, it’d certainly be her. I remember one particular episode where the other friends challenge her to leave her shoes out in the living room, instead of tidying up as she does every day. She’s adamant she can do it – but once she’s in bed, she finds herself obsessing over the shoes. We’re treated to her inner monologue which goes something like: “I can do this. I’m fine with this… Ok, maybe I can sneak out and get them, and in the morning, I can get up early, and put them back before anyone notices…. oh god, I need help!” At this last, she buries her face in the pillow, and the audience laughs. Oh, kooky Monica, can’t let such a little thing like shoes in the wrong place go.

But, to someone with OCD, that’s not funny. It’s very real – and she does need help, if she wants it.

People focus a lot on the compulsive part of OCD. They sort of understand that people with OCD might feel compelled to do certain behaviours, though they don’t really understand why.

What they don’t understand is the obsessive part. The obsessions can be why it is so difficult to resist doing the behaviours. And obsessions often present as intrusive thoughts.

Intrusive thoughts aren’t like normal thoughts, which seem to come from within your own brain. Intrusive thoughts are exactly that – intruders, which appear, alien and demanding, and feel like they come from somewhere else entirely. They often don’t reflect what you feel to be your true personality. But the more you try and push them away, the more powerful they become.

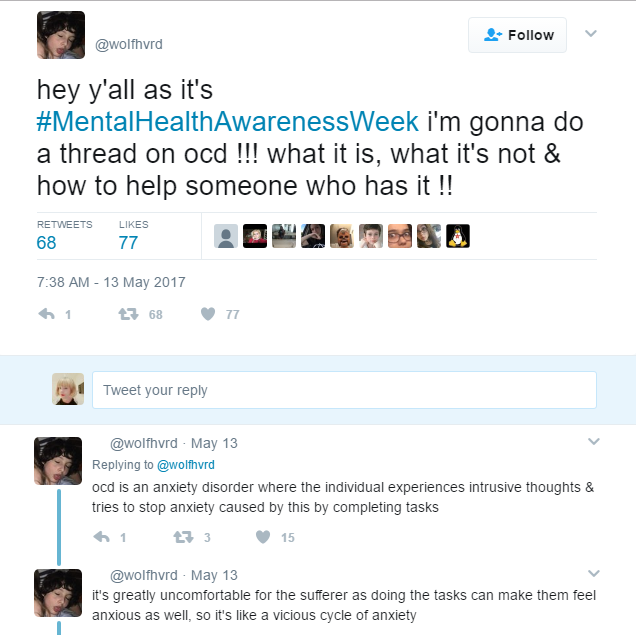

I read a fantastic thread on Twitter yesterday about OCD, which prompted me to write this. You can see the full thread here.

This thread explains how OCD can manifest, why throwaway phrases like “Oh, I’m so OCD” are harmful, and how you can help support people with OCD.

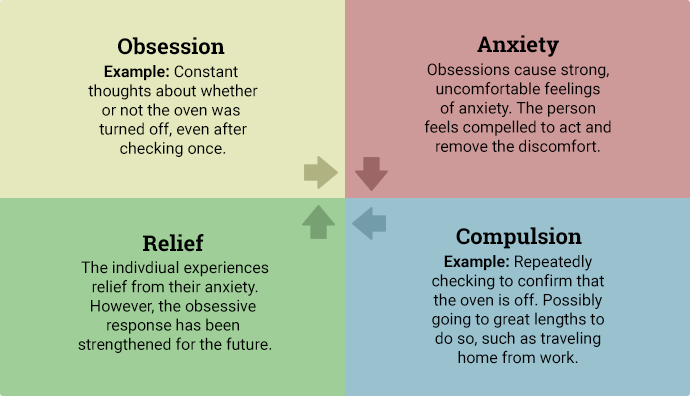

One of the things that stood out for me was where she talks about internalized stigma. If you think of OCD like a circular flowchart, it might look something like:

Intrusive Thought → Need to do a behaviour → Attempt to resist need because of stigma → Anxiety Increases → Intrusive Thought becomes louder →

and so on.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder is primarily an anxiety disorder. The behaviours arise out of anxiety and the need to do something to assuage it, not because you need to do the behaviour in isolation. Monica’s need to have her apartment perfectly in order stems from her anxiety around her relationship with her mother. She is constantly trying to please the older woman, and failing. Even though her mother rarely visits. she still feels the need to exert this perfectionism on herself. She also assumes the role of mother for the other friends. Although it’s safe to say she enjoys cooking and cleaning, she probably doesn’t want to be up all night making twelve batches of cookies in attempt to get a recipe perfectly right, but she finds herself unable to resist the compulsion.

OCD is not just perfectionism, and for many people, it won’t present that way at all. It’s not “being a neat freak.” It’s not quirky and innocuous.

It can be incredibly damaging for the person with it, and for those around them. I know that the people around me sometimes struggle to accommodate my OCD, which leads to me feeling ashamed – but still unable to change the compulsive behaviours. I have even asked my therapist; “How much can I expect others to allow for my obsessive compulsions?” There’s no easy answer to that, of course. People will do as much as they are willing to do.

Often, as I’ve said in the flowchart above, the more I try to resist a compulsion, the worse it will become. Telling myself I am experiencing OCD is of little to no help. I feel itchy at best, suicidal at worst, until I allow myself to complete the behaviour that will stop the anxiety. Sometimes, that behaviour isn’t anything that will look unusual from the outside. It might be getting some work done. It might be taking a shower. It might be going to the supermarket with a very specific list. But what people don’t know or see is that work isn’t even due for another four weeks, but I couldn’t let it sit undone. That I’ve already had two showers today, but I feel like i’m unclean and I need to wash again. That I’ve already been to the supermarket, but an intrusive thought keeps telling me I’ve missed things out or got the wrong ones, so I need to go again.

Again, OCD is, at its essence, an anxiety disorder. OCD can be treated with medication, it can be treated with therapy and routine, and it can be helped by dealing with some of the root causes of the anxiety. But none of that will entirely rewrite the neural pathways that are responsible for causing the challenges.

You can foremost support people with OCD by accepting that, and accepting them. I am very aware of my anxiety and behaviours, and I’m doing my best to manage them. Having someone else try to force me to change would only increase my anxiety and therefore do the opposite.

Remember:

Resources:

OCD on the NZ Mental Health Foundation website