Feminism is meant to be all about body positivity, right? We love and accept other people’s bodies and we love and accept our own. Except it’s not that easy.

I know, in accordance with my politics and my ethics and even my logical science brain, that my body is a Good Thing™. I’m currently reading Clementine Ford’s Fight Like a Girl, in which she repeatedly states: ‘All bodies are good bodies.’ In principle, I agree. When it comes to standing in front of the mirror, I am violently opposed.

I’ve only been learning about feminism for five years or so years, so it shouldn’t come as that much of a surprise that the socialisation of hatred for my body that’s been part of my entire life hasn’t been rewritten overnight. I imagine this is something I will be fighting for many years to come. Maybe forever, because the messages around women’s bodies not being ‘good enough’ are constant, covert and overt, woven through everything we do.

And by ‘good enough,’ we mean ‘good enough that men want to fuck you’ because that is the measure that most women are evaluated by. Our attractiveness is based off our ability to look sexy without being slutty (heaven forbid), looking flawless without any obvious effort (men who compliment us on being “natural” are usually completely unaware of how much much makeup we’re wearing to appear that way), and, of course, looking skinny while also holding a burger – because men apparently like women with steak-and-chips appetites; they just don’t to see the actual result of that.

As much as I would love to say “fuck what men think,” years of being barraged with the idea that my worth is based off whether or not I have a boyfriend have done their job.

The concept of the perfect woman’s body is unattainable, and that’s by deliberate design. If  we aren’t constantly being told that we’re not good enough, who will buy all the products that promise to make us that way? This is how capitalism and the patriarchy work seamlessly to attack women’s self esteem and divest us of power. That’s why it’s a radical notion to love your body – and say so aloud. It’s interpreted as arrogance, when it should be commonplace.

we aren’t constantly being told that we’re not good enough, who will buy all the products that promise to make us that way? This is how capitalism and the patriarchy work seamlessly to attack women’s self esteem and divest us of power. That’s why it’s a radical notion to love your body – and say so aloud. It’s interpreted as arrogance, when it should be commonplace.

Reading The Autobiography of a Female Body helped me to understand the biology of my body, which has gone some way towards undoing some of my negative thinking patterns. But it’s really just the tip of the iceberg.

Of course, for me there’s another layer to try and undo – my body doesn’t work the way I want it to. It’s a body with a disability. And if a woman is not meant to love her body or find it sexy – a disabled woman is especially not supposed to. A look at the body positivity + disability tags on tumblr tells a heartwrenching story. The images of women attempting to reclaim their bodies, reclaim sexiness, reclaim autonomy – and then the comments of those who are tearing them down for daring to do so.

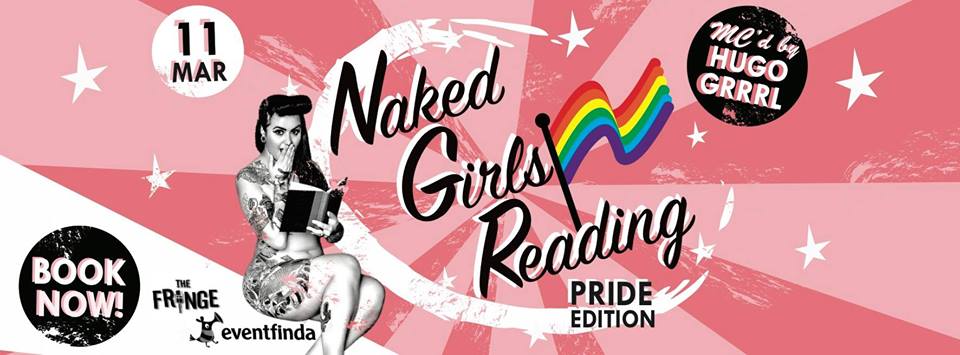

Last year I went to Naked Girls Reading in Wellington, where my friend Polly, who was 7 months pregnant at the time, got on stage in the buff and fucking blew my mind. The event aims at celebrating and normalizing women’s bodies and it was incredible to be part of, especially because the theme of that particular night was LGBTQ+.

Naked Girls Reading is coming in Nelson next month. Polly sent me the link to the organisers asking for participants, with a “?”

I felt sick. A wave of terror rushed through my body, leaving me cold and sweaty. The thought of being in front of people naked was utterly horrifying. I deliberately turn my back on the bathroom mirror when I get out of the shower. If I can’t stand to look at myself – how could I ask other people to?

Hold the phone. Attending Naked Girls Reading was one of the most transformative experiences of my young feminist life. I’ve never been so insanely proud of someone than I was of Polly that night. I felt like I learned so much in the space of two hours and I was part of something bigger than myself. I’ve never attended any Pride events or anything like that, so this was the closest I’ve got to being part of the community. And the whole concept of the thing is everything I believe in.

So didn’t saying no make me a Bad Feminist?

I thought about it hard. I thought about what it might feel like to be on stage (which in itself is terrifying enough) and drop my robe. I thought about sitting there while everyone watched, categorising my every flaw (this is probably not what they’d be doing, but in my mind, they’ve got notepads out and are squinting at the scar I have on my mons pubis). I thought about what I would read and whether I’d be able to get the words out. I thought about whether my friends would come – if they’d be too embarrassed, or if they did and then I’d have to look them in the eye over coffee while thinking to myself: “They’ve seen my vagina.”

Getting to the bottom (heh) of why I hate my body is much harder than just saying “capitalism” or “patriarchy.” For women, our bodies are not just vessels for our minds. They are a form of social currency. We want them to be of high value, and everything we do to or for them reflects that. Unfortunately, that value isn’t easily chosen by us. Valuing ourselves is a political act, because we have to choose to do so even when our parameters don’t match the unattainable thousand dollar note.

Getting to the bottom (heh) of why I hate my body is much harder than just saying “capitalism” or “patriarchy.” For women, our bodies are not just vessels for our minds. They are a form of social currency. We want them to be of high value, and everything we do to or for them reflects that. Unfortunately, that value isn’t easily chosen by us. Valuing ourselves is a political act, because we have to choose to do so even when our parameters don’t match the unattainable thousand dollar note.

My parents taught me to value myself – but society taught me otherwise. Disney taught me that I needed to be a hidden princess with tiny feet in order to capture a man’s attention and earn myself a happy ever after. I remember asking two popular girls at primary school if I could be their friend, and being told “No, you are too fat and ugly.” I was eight.

That refrain, while never articulated quite so boldly, echoed throughout my teenage years. I wasn’t popular, and never would be, because all of the popular girls were “pretty,” and had boyfriends.

Like most teenage girls, I yo-yo dieted, obsessed about clothes and makeup, started dying my hair at 14. I haven’t been my natural colour since. As many of you know, I now have extensions because of the chemotherapy. Nothing was ever good enough.

Getting sick was another nail in the coffin of my self esteem. Attempting to love your body when it is actively rebelling against you is incredibly difficult. Why would I love this thing? I ask myself. It doesn’t even work properly! Forget pretty, I’d just like to achieve some basic tasks!

Overriding that feeling is my journey. I read a thing about women learning to love their bodies not because of what they are, but because of what they can do. They began to respect their bodies when they took up weight training, for example. While what I can do is still heartbreakingly limited, I can see the merit in this idea.

Meanwhile, I had to reply to Polly. “I can’t do it,” I said. “I’m a bad feminist.”

I felt ashamed of my fear. I didn’t want the patriarchy to win. I wanted to be the sort of woman who stood tall, scars and stomach and illness and all, and owned my nakedness. But I knew that agreeing to this would cause the sort of intense anxiety that would incapacitate me for weeks leading up to the event, and I couldn’t put my life on hold, or subject my body to that stress. Loving my body, in this case, meant accepting what it needs.

Polly pointed out that knowing your limits and sticking by them is also a feminist act.

I have to do that for now. But watch out, 2020. You just might be the year I find that stage.

And then we can talk about my vagina over coffee.