It’s Mental Health Awareness Week in NZ. I am unwell. This has provoked some thoughts, which I have been avoiding sharing because they are messy and complicated – just like this topic. But; let’s go.

This time last year I wrote about statistics and waiting lists and the Total Lack of Real Support in this space. Nothing’s changed. In fact, this year’s suicide statistics are the worst on record.

New Zealand right now not only does not have any fences at the top of the cliff – the ambulance at the bottom is a clapped-out Holden ute with a Lilo in the back and a first aid kit with a couple of panadol in it. – Me, 2013, shortly before going into Respite care.

Despite the government saying “lots happening in this space!” (literally a tweet I received from a National MP) – I am failing to see what. All I see is the loss of Relationships Aotearoa. The loss of free counselling for Christchurch quake residents. The dwindling resources for Women’s Refuges and services like Lifeline. The massive ACC waiting lists, which people are continually cut from.

The age group with the highest number of suicides is the 20-24-year-old group, with 61 deaths, followed by the 40-44-year-old group with 58 deaths. Maori suicide is also at an all time high with 130 recorded in the last year up from 108 recorded in 2013/2014. source.

What concerns me is the sorts of resources that are being cut and underfunded are the “in between” ones we really need. What’s an “in between” service? Here’s a thing I wrote a few months ago:

“For me, and for others judging by my research, there are around three different degrees of managing mental illness. One is when you are coping fine. You consider yourself stable, and you have the support you need. Two is when things become harder and you need more help – perhaps increased therapy and/or medication. You might have thoughts of self harm. You might feel like you’re not really stable or coping. Three is when things become unsafe. When your illness has overwhelmed you. When you seriously consider, and or attempt, self harm,

It is easiest to get the help you need during stage One. You’re capable of being on waiting lists for therapy. You’re capable of changing medications if need be.

During Two, things get more difficult. You need support more urgently. But because you’re not quite suicidal, you may not get it. And because of the stigma involved in asking, you may not ask.

Then you hit Three. At this point, urgent care can be accessed. But my own experiences and my research show that too often, it’s too little, too late.”

Services like counselling and often psychiatric support are needed most during Stage Two, the “in between” resources.

Despite the fear it causes me, I will be honest. I have been in Stage Two a lot, and I’m in in now. I know a lot about looking after myself. Because I did get to Stage Three in 2013, I was able to access a psychotherapist, and that therapy saved my life. No, not hyperbole.

But, because of the various stresses of my disability, studying, and interpersonal relationships combined with my depression and

generalised anxiety disorder, I’ve slipped backwards a little. So I started hunting for some support, for two reasons, A) Someone to talk to, and B) An expert to assess my medication, which is a completely different mix since the last time a psychiatrist looked at it.

I asked my doctor for a referral back into the clinic I’d been in before. I’m well aware of how long their waiting lists are. That referral has just reached them, six weeks later. The first available appointment to see a psychiatrist is in December.

Student Health couldn’t offer a counselling appointment for three weeks, by which point I’ll be in another city.

I ended up realising the only way I’m going to get help is to pay for it, so I have an appointment with a psychologist set up in two weeks, and I’m just hoping WINZ might put some resource towards that.

This story is not unique. Services are overrun and underfunded. And we don’t like to talk about it.

This is a fucking awesome vid from John Oliver on the need to talk about mental health, the language around it, and the specific shittiness of the US mental health system, which is basically not existent.

What happens so often is that people – I mean people, not services – do not know how to respond to distress. This is normal. What do you say to someone who says “Everything is shit and I don’t know what to do”? And the ‘right’ or helpful response will of course be different for everyone.

Moira Clunie, of the Mental Health Foundation, said everyone needed to think more carefully about how they could prevent suicide, particularly among Maori and young people.

Research showed most people who attempt suicide do not want to die but felt they lacked any other options, she said.

“If you’re worried about someone, asking them about suicide will not increase their risk, but ignoring their distress can. For a person who is struggling, having a chance to talk to someone who will listen without judgement can be a great relief.” source.

For me, the absolute worse response is silence. Or this.

I totally recognise that people talking about their mental health can be triggering for others, and that people will not always have the resources to respond. But if I say I need help – to a friend, online, to my doctor, to any mental health service – and I get nothing back? That’s bad territory, right there. That’s bad shit.

There’s a really fine line here. There’s three things that need to happen for someone to get well:

– They need to help themselves. This is non-negotiable. There is no point people throwing ladders down to you if you will not climb out of the hole.

– They need the support of their friends and whanau.

– They need the support of the medical and mental health system.

There needs to be a good balance between all of these things. I read this amazing, amazing article about resilience the other day. Like holy shit it really changed my view on the whole idea of resilience. It’s quite like, academic, but it’s short. Here’s an excerpt:

Resilience discourse treats trauma and crisis as compulsory experiences. In turn, this lets society off the hook for systematic problems like poverty, climate change, and sexism. Resilience discourse outsources the work of addressing, surviving, and coping with the harms of systemic, institutionalized inequality to private individuals.

If you still feel the negative effects of, say, sexism, it’s your fault because you’re just not resilient enough. Society doesn’t have to spend any resources solving or alleviating harm, nor does it have to put any more effort into reproducing the relations of inequity that cause these harms. If everyone has to experience some loss and damage, the people who began with more resources and more access to privilege will always have an easier route to recovery–and often a more successful outcome–than those without.

The main thing that distinguishes resilience from other forms of coping is that resilience ultimately benefits hegemonic institutions more than it benefits you,

Basically, this is saying “put up and shut up. This stuff is normal and happens to everyone. Deal with it.”

Nope. I’m not having a bar of that. You don’t have to put up and shut up. You should not be expected to cope alone. “Resilience” is a romantic ideal and it’s one that’s enforced by the state. (Just look at Christchurch and its people).

And you should also not be expected to always “reach out.” This is one of my absolute favourite pet hates – “reach out.” I have literally just described my experiences when I reach out. I get: waiting lists. I get: stigma. I get: silence and fear.

So, you don’t need to go it alone – but you do need to acknowledge what’s happening, and to want to get better.

You also need people around you to recognise and acknowledge what you’re going through. This comes back to stigma and fear. When I talk about mental health on Twitter, here, anywhere really, it’s extremely hard. I am extremely anxious about it. And a lot of the time, I get silence back. Because it’s really, really hard to know what to say.

I don’t have the answer to this. Sometime, I send people stupid cat pictures. Sometimes I tell them I love them. I try not to tell them things like “I know what you’re going through,” because I don’t. I just try to do things that say: I see you, and I love all of you.

Finally, you need the help of the system. We’ve been through what that’s like. It’s Stage Three or it’s waiting lists. Or it’s $100 an hour psychologists who also have waiting lists, because more and more people are turning to the private sector for help.

Phew. This is long, so if you’re still with me, thank you.

I have a couple other things I want to share before I wrap up.

Here’s a post I wrote about the book and blog Hyperbole and a Half. Those comics have been a wonderful tool for teaching myself and others about depression. I refer to that book a lot.

And here’s an amazing post on Captain Awkward by Elodieunderglass about coping with low moods. It is written in very real language and the illustrations are great and I found it really helpful, so others might too.

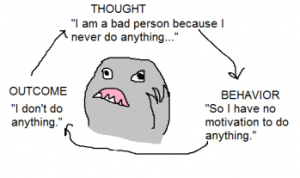

Quick example:

“If you’re in a bad place, this is one way that the cycle of badness continues to percolate in your head. And we’ve all been there – we’ve all seen how Low Mood affects your health, productivity, relationships, creative output, and mental outlook. Which is to say: A good deal of your life.

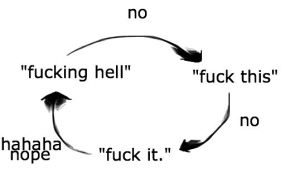

or if you’re me, it’s a bit more like:

This illustration spoke to me on like, a deep emotional level.

Ok yeah. That’s it. That’s all I have. Mental Health Awareness Week.

– WH

Pingback: Just slacktivism? | Writehanded