If you’re a person living with mental health challenges or mental illness, you’re probably very familiar with the many hurdles you have to jump to get help. Are you sick “enough”? Should you see someone? Should you try medication, and if so, what sort? Can you afford it, or do you qualify for subsidised services? How does one actually “reach out?”

I stumbled across this article by Hanna Brooks Olsen this week, and I’ve read and reread it, each time coming across something new.

Hanna has bipolar disorder. She’s tried different medications, different doctors, struggled with the bureaucracy of mental health systems – and written her experiences and thoughts.

After years of trying to hold everything together on my own—to be what I thought of as strong and capable—I could acutely feel myself beginning to unravel. At that exact moment, I couldn’t be bothered to put on airs any longer, nor could I continue to creep around the problem; I needed psychiatric care, I needed it soon, and I needed a complete stranger to help me with it.

I think it’s incredibly gutsy to write something like this. Mental health carries massive stigma, and sharing your truth makes you

Hanna Brooks Olsen

vulnerable. As Hanna says, the first fight is getting past yourself. We’re taught a narrative of strength that at it’s simplest discounts medication and therapy, and at it’s worst will actively discourage asking for help.

I knew I had depression by age 12. But I spent the next six years telling myself “I don’t have depression, I’m just sad. It’s ok to be sad.” To me, it wasn’t ok to be depressed. Depression was a life sentence. No one wants to be around someone with depression.

Obviously, none of that was true. But admitting I had a mental illness and agreeing to trial medication at age 18 was one of the lowest points of my life. And it shouldn’t have been. I should have been able to say – to anyone – “Hey, I have depression. Isn’t it awesome that I can access medication that will help me balance my brain chemicals and live a better life?”

Yeah. I don’t know that I have ever said that.

A couple of years of medication attempts and failures and finally some stability later, I received a card that said “I hope one day you can manage without the pills.” I am sure the sender meant this with utter sincerity – an acknowledgement of my bravery and my clear, illness-free future.

What it said to me was: “You’re being very weak right now. I hope you’ll stop that soon.”

I’ve seen a lot of people say “Medication is just a crutch!” like this is a bad thing, and every time I squint really hard and go “huh?”

Crutches are good. Crutches allow us to walk when we otherwise may not be able to. Crutches support us. No one would go up to a person with a broken leg and be like – look buddy, I really think you’re relying on these too much, time to get that broken thing going on it’s own – and yank their crutches out from under them. Because that would be atrocious.

And yet it’s somehow ok to suggest this to people who use medication to manage their mental health.

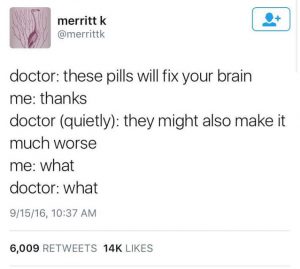

Finding the right medication isn’t easy. It’s trial and error, and those trials can take months. I’ve lost count of the number of pills I’ve tried, with the fervent hope that this time, this one, will be the one to stop my brain from constantly sabotaging me.

At the moment I’m attempting another change, simultaneously going off one drug and onto another. It’s the pits. There’s no bones about it. The mental and physical withdrawal symptoms, the side effects, the pushing through each day with no actual guarantee that there’ll be a positive outcome – it all sucks.

And as for the therapy side of it, well. As Hanna said: “I needed psychiatric care, I needed it soon, and I needed a complete stranger to help me with it.” You do have to trust strangers. You do have to open yourself up so someone can take a look at all the little wonderful secrets curled up in your entrails. You do have to hand those secrets over as they hiss and snarl and catch against your ribs. And that’s if you’re lucky enough to actually be able to access a therapist.

The barren truth is that mental health care — finding it, getting it, taking part in it, complying with it — is work. It’s labor. It’s hard for high-functioning mentally ill people like me, and it’s impossible for those who aren’t functioning quite so well. For millions of people without health care (which was me for a lot of years), it’s simply inaccessible.

Hanna unflinchingly addresses some issues I’ve raised before in the New Zealand context. Yeah, the mental health system is broken, and we’re past the point where it’ll be fixed by throwing money at it – like anyone in our government is interested in doing that. But even if it weren’t, even if you could get help easily and quickly and cheaply by raising your hand and saying “yes, me over here please” – would you?

We often see the phrase “reach out.” Again, the system is broken, so there’s no guarantee that reaching out would result in anything except frustration and despair. I’ve called for help and been told I’m not bad enough to warrant it. I’ve called for help and been ignored. I’ve called for help and had diets, oxygen chambers, and “thinking positively” offered to me.

In New Zealand, the ambulance is at the bottom of the cliff, and it’s not even an ambulance, it’s a clapped out Ford ute with more rust than paint and a half-deflated lilo in the back.

Reaching out implies you can. It implies you know you need help, and you want it. It puts all the onus on the ill person. And, as I said – it doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll get help.

We need a new approach. I wrote about this two or three years ago after Charlotte Dawson’s death: “Reach in.”

Reaching in would be a whole lot easier if the organisations working in our communities weren’t so utterly decimated by funding cuts. They don’t have the staff to do it.

It’d be easier if people were taught about mental health, what to notice, and more work was put into changing the belief systems surrounding it. We don’t have the budget for these campaigns.

It’d be easier if people who need help hadn’t been knocked back in the first place and become understandably cynical.

But if you’re a person, or an organisation, with the privilege and resources, to do it? Do it. Reach in. As I wrote three years ago: “Words may be the one thing that change the journey for someone who is suffering.”

Thank you to Hanna for sharing hers.