Someone told me about Trish Harris’ The Walking Stick Tree – a memoir by a woman diagnosed with Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis when she was six – a week ago, and within a couple hours I had bought it and was half-way through.

It’s unusual to find a book that confronts chronic pain and disability so plainly, and rarer still to find one that does so in a New Zealand context. The Walking Stick Tree is an episodic journey interspersed with critical essays about pain, loss, illness and identity. As much as I was interested in Trish’s early experiences of arthritis, the essays were particularly valuable. The tone of them was reminiscent of some of Stephanie de Montalk’s work in How Does It Hurt?

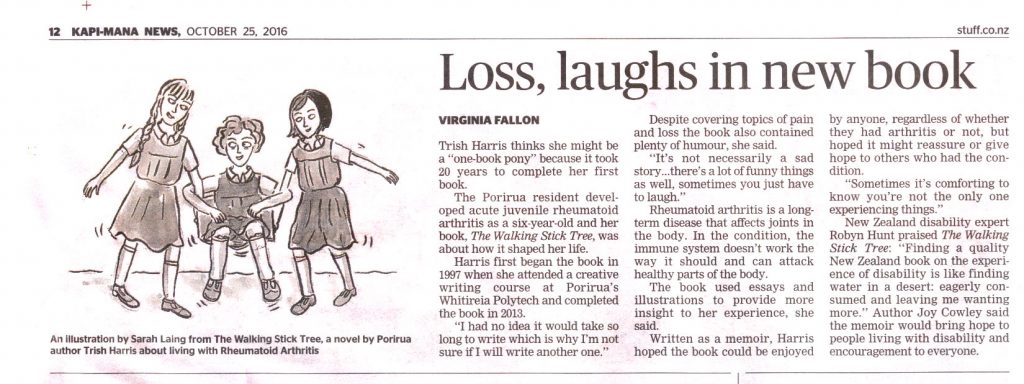

In an interview with the Southland Times, Trish says “I hope my book connects with other people’s stories. Even if the circumstances are different, often the emotional story is similar.”

This is certainly what I have found to be true, in my work sharing my own and other people’s stories of illness or disability. Everyone has their unique challenges, but there are some universal feelings, some identikit frustrations, some shared tremors that do not need to be spoken; the metaphysical nerve pain deep below the surface.

I spoke recently with a woman who was sent home from hospital with the words: “Your pain is all in your head.”

Trish Harris

Well, of course it bloody is. And, of course, it isn’t. It’s inescapable; everywhere, and yet completely effervescent.

Getting at the nature of chronic pain, tapping its source, can be incredibly tricky. To describe it to yourself is a feat – to describe it to anyone else an academic improbability. Steph de Montalk spent a four-year PhD attempting it. I have written and deleted so many sentences that come nowhere close to describing my physical and mental experience. Sometimes, the more I talk about pain, the worse it gets.

“When I was a teenager, I can remember fantasising that someone would ask me how much pain I had. ‘I’ll tell you every time it hurts,’ I’d say. Then I’d say ‘Now.’ ‘And now.’ ‘And now.’ All I’d ever say was ‘Now.’”

Trish isn’t in pain any more. She describes this as the disease having “burned itself out.” I don’t know what this means exactly, but as a fellow sufferer of arthritis, I wonder if it will happen for me. Will it be me or the illness that burns out first?

The Walking Stick Tree, along with telling the story of Trish’s life, contains the essays ‘The nature of pain,’ ‘Exploring loss, sadness, and grief,’ and ‘The dance of identity.’

In the first essay, Trish describes pain as a force. “In the end, this force carves away spaces inside. Everything runs up against it, everything is thrown back from it, like the bullish sea against the coast. It is by nature an excavator, taking away and reforming what is left.”

In the second, she says “Sadness, grief and loss are not always given much air time in the disability community. Maybe there are just too many variations on the ‘sadness’ story. Where would we start and who would have room to listen? Maybe we are so busy proving what we can do in light of what others think we can’t do, that it can be hard to make that journey to our vulnerable self. As the predominant view of disability in society is that it’s a tragedy, who wants to feed into that? I wonder too if it fits into a wider ‘think positive’ ethos. We dare not mention loss without rushing to say there is also gain. And how do we go near loss if we can’t fix it?”

“Gaston Bouchelard is more adamant. He says. ‘What is the source of our first suffering? It lies in the fact we hesitated to speak. It was born in the moment when we accumulated silent things within us.’”

I feel kinship with this. As someone who is constantly encouraged not to dwell, not to share too much, to be positive – I want to beg for the space to grieve. For others to accept that I have lost. For them to see that this is my narrative, and I am allowed to own my sadness about how my life has been so viciously changed.

In ‘The dance of Identity,’ Trish says “Identifying with the label of disability isn’t a one-off experience. If I look at my own reactions and choices, there’s a constant dynamic tension between the need for both acceptance and denial. To claim the full reality of living in this body can still be overwhelming.”

She talks of the fight with self-stigma – how to accept disability without that becoming everything you are.

Pat Rix, one of the presenters at the High Beam festival in Adelaide, said in her rap: ‘Never let a label put you in a box / Living is an art and art unlocks.’

“Labels can box us,” says Trish. “‘There is more to me than this!’ I have wanted to yell many times. Yet I know the exhaustion of trying to keep up, the inevitable consequences of pretending my energy levels are normal and my mobility easy. This is where it’s hard to know how to claim this disability in a life-giving way.”

I too know this exhaustion.

In the last chapters of the book, Trish’s writing becomes somehow braver, stronger, and more lyrical. She shares the tale of doing the Central Otago Rail Trail in a motorised wheelchair.

“On the second day, the gully wind hits. We need every layer of clothing. I need gloves as well. The ground is a dusty, pale yellow, mustard, light brown. No culverts or embankments, but a groove cut into the land. Cyclists emerge through the gap with their helmets, bright colours and a surprised look. A smile, a ‘hello’ as they pass me. The trail is the width of a train, wide enough for a wheelchair and a bike; for two lane traffic. In the Upper Taeri Gorge I feel like I’m in the Grand Canyon. A tree offers me it’s first born, a yellow leaf propelling its way towards me like a kiss. I have arrived in Wonderland.”

Ironically, after completing the Trail, Trish was refused passage on the bus home – they said they had no room for her wheelchair. This despite being capable of taking innumerable mountain bikes. She laid a complaint with the Human Rights Commission, but after two years of battling, she ran out of energy and withdrew it. A friend said that this was ironic. “If you have to go through all those hoops to get something resolved, it’s not really a human right, is it?”

Bureaucracy is a terrible, ongoing, inescapable part of chronic illness and disability. If it’s not WINZ I’m talking to, it’s ACC, it’s another form to fill out, another letter to anxiously rip open.

Trish talks about writing multitudes of forms to seek assistance with remodeling a car so she could use it with her wheelchair.

“I filled in all the forms: I detailed my life, my finances and my medical condition. On one form, there was a question that made me cry. Not only did it ask why I needed the car and the crane, but it asked how it would make a difference in my life.

Here was a place I could tell my story on my own terms, rather than trying to pole vault myself over another set of criteria.”

Telling her story must have done the trick. Trish’s got her car, and she cites that as life-changing.

Freedom. A thing so often stolen by pain and disability. It should never to be underestimated.

The Walking Stick Tree was published by Escalator Press last month. EP is an imprint set up by the Whitireia Creative Writing Programme.