In poems, space is just as, and sometimes more, important than words. In real time, Ground Control attempts to reach my brain, finds only static. ‘The circuit’s dead, something’s wrong.’ I’d like to explore but we’re in (self) critical condition. The mission to communicate continues…

My mind is spaced out enough without adding physics to the mix, but sometimes parallels occur without attempt. Unlike this post, which has taken untold hours to patch together.

I began with David Bowie’s Space Oddity. Stuckness and loss, confinement and freedom, chilling isolation soothed by mundane routine – all trailing to that haunting yet peaceful end. Bowie himself said the song ‘never really had a direction…I don’t think that I, as the artist, had a focus about where it should go.’

Of course, Bowie unfocused is still Bowie, and perhaps the genius is in the askew unfolding.

In 2005, the writer Stephanie de Montalk had returned from her own odyssey, though within orbit. Her story an apparent pairing with the fictional Major Tom; a promising trajectory toward cool peace, the gritted sentry setting forth – only to succumb to stillness. To the severance of connection with control.

I’ve spoken many times about Stephanie in the seven – eight? – years since I attended the launch of her autobiographical textbook on the communication of pain in 2014.

How Does It Hurt?, the result of Steph’s PhD, would be a remarkable accomplishment for anyone. Though it comes to a depressingly inevitable conclusion – that there are no adequate means to truly know another’s pain – it is, at its heart, an embodiment of empathy.

This speaks of the writer herself. In 2003, in a bathroom in Poland, Steph fell. The resulting and ongoing injury was rare; only two doctors in the world were willing to attempt to operate. Steph chose France.

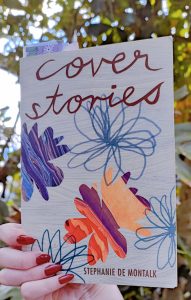

The surgery and its aftermath are themes threaded delicately through her 2005 poetry collection, Cover Stories.

Two or so weeks ago, I was rummaging through dusty shelves in a recycling op shop next door to the dump. I don’t usually look for books, primarily using my e-reader, but have recently been hunting battered Mills and Boon paperbacks – the romance I cut my teeth on in my teens. Part nostalgia, part research.

That day, though, the treasure I would find was not amusingly banal fiction, but something far more valuable.

A perfect copy of the collection, written in the months after the French surgeon failed.

I called Steph, who was pleased and slightly surprised to be reminded of the book she’d created from within a fog of pain sixteen years ago. This is an experience we both understand. Pain shrouds the brain.

This is the first day I have sat at my computer since July. Following my wedding in April, I threw myself into my new writing project with gusto. Too much, perhaps, as it quickly became clear the work is, at this time, unsustainable. The devastation, frustration, and shame I experience when unable to write is a pain all of its own. But the physical pain was, and still is, in control. Like Major Tom, I am existing in an ether of disconnection. My body refuses to move, fatigue weighting each limb. I am constantly aware of my spine, my shoulders, my hips. My brain is swollen and slow. I lose track of conversations before I am able to begin them, and quite often in the middle. Those around me must repeat themselves; I write everything down and then forget to check. I set notifications using Google, I use the calendar on the fridge. I trawl through my memos app and the two notebooks beside the couch. Still, words elude me. Stringing sentences becomes an Olympian task.

And I have lost the companion who kept close through all my years of illness. Carina. In addition to the physical pain of sitting at my desk, doing so is a sharp reminder of her absence. No matter how many times I attempted to fend her off, she always managed to ease her way onto my lap, squeezed like an oversized tube of toothpaste between my belly and the keyboard. Half the time, I wouldn’t even realise she’d done so until my shoulders began to ache from angling my wrists over her purring head. I could rarely deny her anything. In the last weeks of her life, when we knew the inevitable, we pampered her to almost complete absurdity. Expensive steak, sliced thinly, offered from my fingers. Shreds of cooked chicken breast, bowls of illicit cream, fresh fish by special order. Most of the bed, and breakfast as early as she decided it.

I have never experienced my illness without Carina by my side. In these last weeks, laid low with exhaustion and confined to the couch, the ache of loss has been acute. A comfort I relied on, a light in the endless boredom, an unconditional love, and never an expectation of memory or conversation. Never the fatiguing, fumbled explanation of all the things I cannot do. She just cared that I could be.

It is day three of attempting to write. I have noted with irony the words in the bottom toolbar of Microsoft Word. ‘Accessibility: Good to go.’

I could argue the fact.

I have given up on the desk and retreated to my corner of our large grey couch. It contains a multitude of pink pillows I can stack and rearrange into a sort of cradle. It is not ergonomic in the slightest and my neck will soon ache from angling down to the screen. I have yet to find any situation or position in which I can write without pain.

Steph de Montalk, who is unable to sit, researched and wrote the entirety of How Does It Hurt? laying down. To think of it beggars belief. Hers is an indomitable spirit. Her husband John refers to her as indestructible.

However, when I phone with the news of having found Cover Stories, she recalls well the state she was in while creating the collection.

The French surgeon had failed. Her physical pain was barely under control with inadequate medication, and her mind was full of frustration and something far deeper than disappointment. Yet word by word, she persisted.

I am, as always, in awe. ‘Comparison is the thief of joy’, etcetera, and yet I chastise myself – why is it that I cannot harness my own pain? Is my spirit so weak? Must I just try harder, as instructed by the protestant marriage of capitalism and classic kiwi ‘she’ll be right / toughen up’ attitude?

“…the Protestant understanding of man is that the believers… are to follow God’s commandments. Industry, frugality, calling, discipline, and a strong sense of responsibility are at the heart of their moral code.” – The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789.

I fight self-loathing. Messages stack up on my phone – friends reaching in, sharing news, asking of my condition, gently suggesting opportunities. I am too tired, and too anxious to reply. Making plans frightens me, as I can never predict my level of ability, and cancelling only feeds inadequacy. Instead, I have retreated. Even my online presence has proved too difficult to maintain.

My primary occupations are the basic functions of looking after myself, my husband, our house, and myriad health and life administrations. I find joy in small things; feeding the birds, growing monarch butterflies in a small swan plant grove, reading ridiculous romance novels, dying my hair pink and sharpening my nails to unicorn-coloured points.

And, of course, as always, poetry. A different way of looking at the blue earth, the stars, my own drifting and disconnected existence.

It is 5.30am on a Sunday. After sleeping restlessly through medication-induced nightmares and the ever-present pain that spikes every time I roll over, I’ve given up and retreated to my couch fort. It’s taken me half an hour to edit my last paragraph and write this one.

Again, I think of Steph. I have issue with the adjective ‘inspiration,’ – there is an uncomfortable and often offensive trend of people with disabilities being held up as an example to able people. Steph is not my inspiration, she’s my co-conspirator. A rare person who can truly empathise. A leading light in my darkness and an encouragement. I, with courage fraudulently tattooed on my left ankle, require the hope engendered by Steph’s ability to create from within the hostile environment of persistent pain.

Poetry would appear the perfect form when one does not have the energy for a multitude of words. However, all poets know the effort required to choose the right one, to edit, edit, look away and come back and edit again.

I am rebellious. I never start off reading a poetry collection from the beginning. Instead, I prefer to open a random page and see where it takes me. Akin to skipping Bowie’s later work in favour of Space Oddity, first released in 1969, owned on vinyl by my father and very recently inherited by me.

I opened Cover Stories at page 30…

**Look out for Life in Space: Chapter Two, (brain willing), next month.**

That’s just a perfect piece of writing. I can’t know all your pain, although I feel your pain from Carina’s passing acutely, but you give me an idea, perhaps the essence of what it took to write this piece.

Kia kaha Sarah, we are blessed that you can write; and write so beautifully.

Thank you so much Kev. It did take a lot to write, so it therefore means a lot to know how it’s being received – and that anyone is reading at all tbh.

Thank you for being someone who continues to encourage me.