In some ways, I am not the best person to write about this book. I am wary of taking up space with my Pākehā voice. Not everything is for me, and I know there are depths in this work that I won’t full appreciate or comprehend. But I think it is very special and very, very good, and so here we are.

I had the luck and honour of studying with Tayi Tibble (Te Whānau ā Apanui/Ngāti Porou) in an undergrad poetry course at the Institute of Modern Letters in 2015. She is a perfect storm of a person; the literal embodiment of ‘containing multitudes.’ She takes no prisoners and never blinks.

Having been party to that earlier work, I had high expectations, and still I was surprised. She was the recipient of the Adam Foundation Prize after completing her MA in Creative Writing. I know she’s good.

This book is… something else.

As seemed fitting, I decided to read it in the bath. I meant to get through a few poems and then set it aside.

By the time I turned the last page, the water was cold.

*

Usually when I’m reviewing this sort of work, I don’t know the author. The fact that I do inevitably altered my reading, which is not necessarily a bad thing. Impartiality in art is a myth and everyone will bring their own experiences and preconceptions to the work.

What it does mean is that I’ve found it impossible to write about the book without writing about Tayi herself. And I guess that makes sense, because poetry is deeply personal and this is personal work.

What I don’t want to do is bracket her or her work with any of the obvious identifiers.

It’s important to write what you know, we all learn that. But does writing what you know pigeonhole you? Michalia Arathimos’s PhD research into the representation of ethnic writers in New Zealand media found that the ethnicity of Witi Ihimaera and Keri Hulme was mentioned 100% of the time.

She recognises that this is an issue with layers, saying that sometimes labelling is important, especially to increase representation.

“…if writers are addressing culture in their writing, then we need to know where they’re from to contextualise their work.

…The problem comes about when the mainstream press takes these identifications and parrots them with little awareness of positioning or context — and the label becomes a selling point, or, worse, the only interesting thing about that writer. Then the writer becomes a part of what we can call “the postcolonial exotic”…”

By acknowledging this rhetoric, I hope I signal my desire not to be part of it. It is also impossible to write about Poūkahangatus without naming the context of Tayi’s heritage. To do so would be to miss the point.

*

After our workshops, I used to scroll through Tayi’s work online – very popular, often more explicit than what she shared in class, which already pushed at the margins of acceptability inside the hallowed white walls where we studied.

The problem with being young and Very Good is that everyone focuses on the fact that you’re young. ‘So much potential,’ they say, thrilled at all the things you might become, congratulating themselves on having noticed, and wilfully ignorant of the things you already are. It’s a gendered devaluing that happens to talented women, whether they’re 25 or 30 or 50.

‘So much potential,’ they say, thrilled at all the things you might become, congratulating themselves on having noticed, and wilfully ignorant of the things you already are. It’s a gendered devaluing that happens to talented women, whether they’re 25 or 30 or 50.

This devaluing happens about fifty times as worse if you’re young and beautiful.

Some of Tayi’s work is about being young and beautiful. About what happens when older men see your talent and want… that.

Some of it is about being young and not feeling beautiful at all, part of which is to do with white coded ideas of beauty.

I can’t remember what poem it was in or when, but some time ago I wrote the line ‘this is my/ inheritance of guilt.’

It is not at all the same, but there is I felt guilt in the pages of this book – warranted or not. There’s the guilt of the narrator about their interaction with their own heritage, but there’s also a finger pointed squarely at the white reader. I want to acknowledge that I felt that, even if I a) am unsure how to address it, and b) though I’m in the role of reviewer here, I am aware of trying not to make it about me.

*

One of the interesting things about Tayi and her work is that it’s not always clear when she’s telling the truth – which is of course poetic licence and a mark of a good writer; if she can convince you she’s telling you her darkest secrets when actually she’s telling you something she overheard in a movie theatre and liked the sound of. Truth is not necessary for good work.

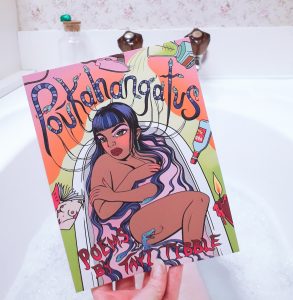

Even the title is a creation. ‘Poūkahangatus,’ Tayi says in the notes, ‘is a hybridised word of my own invention, phonetically mimicking ‘Pocahontas’. It has no literal Māori translation, though ‘pou’ in te reo Māori means pillar or pole, and ‘kaha’ means power or strength.’

In the movie, Pocahontas remains in America. In reality, she became an important figure in relations between Native Americans and colonisers, which lead to her leaving the country and dying far from home. I guess that’s not the romantic tale Disney wanted to tell.

In the book, she appears in the first poem – ‘An essay on indiginous hair dos and don’ts.’

In 1995 I was born and Walt Disney’s Animated Classic Pocahontas was released. Have you ever heard a wolf cry to the blue corn moon? Mum has. I howled when my mother told me Pocahontas was real but went with John Smith to England and got a disease and died. Representation is important.

I was equally and appropriately gutted by ‘Sensitivity’ –

248 years

since Captain Cook

landed

14 years

since Whale Rider was

released

Keisha Castle-Hughes

is speared through the heart

by a white man with a ship

in the television series

Game of Thrones season 7 episode 3

52 minutes and 22 seconds in.

For me, there is a constant undertone of discomfort in Poūkahangatus. It’s a slightly queasy feeling fed by carefully chosen words, images of vulnerable young women, of marginalised identities, hangovers, cigarette stains. I think it’s highly intentional that I feel that way.

On the flip side, there’s also beauty and opulence. Literal rose gold bathtubs full of champagne, sex, danger. High stakes and higher payoffs.

To balance the two takes skill and clarity. It’s a collection that is exploring, but it’s also already come home.

As is usual, it’s difficult to narrow down bits to share. But I want to finish on the last lines in Mint-Green Cross, which describes hunting for treasure in a second hand store.

Sometimes we say we hate David White, what with him being an inconsiderate hoarder and all. The only decent thing I ever got here was a white bell-sleeved dress that didn’t fit. Sometimes I want to scream at him, you can’t just call your problems something beautiful like a gallery, David.

The book will be launched by VUP in July.

“This collection speaks about beauty, activism, power and popular culture with compelling guile, a darkness, a deep understanding and sensuality. It dives through noir, whakama and kitsch and emerges dripping with colour and liquor. There’s whakapapa, funk (in all its connotations) and fetishisation. The poems map colonisation of many kinds through intergenerational, indigenous domesticity, sex, image and disjunction. They time-travel through the powdery mint-green 1960s and the polaroid sunshine 1970s to the present day. Their language and forms are liquid-sometimes as lush as what they describe, other times deliberately biblical or oblique. It all says: here is a writer who is experiencing herself as powerful, restrained but unafraid, already confident enough to make a phat splash on the page.”

– Hinemoana Baker