“Being told that, categorically, he knows what he’s talking about and she doesn’t… perpetuates the ugliness of this world and holds back its light.”

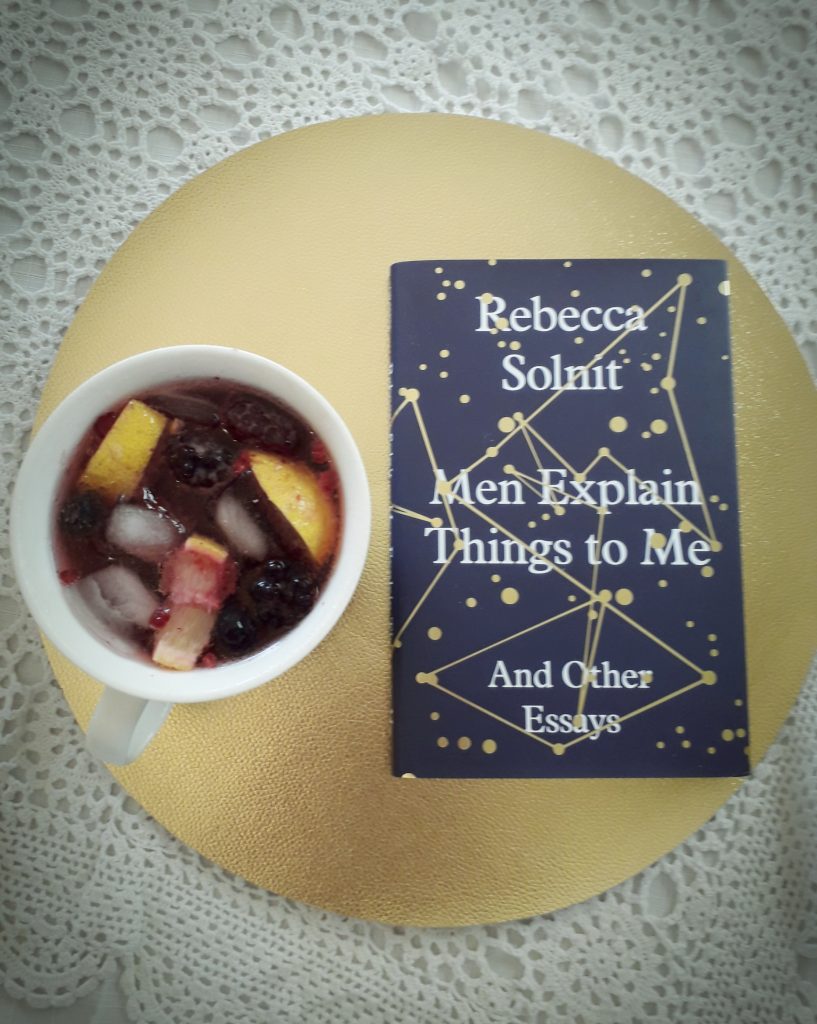

Author Rebecca Solnit is credited with coining the term “mansplaining” – to describe when a man explains to a woman something she already knows – and probably better than he does.

In the title essay of Men Explain Things To Me, Solnit recalls a time at a party where a man, not listening to either her or her friend’s interjections, attempted to explain a book to her. The only issue was that Rebecca had written the book.

“Men explain things to me, still. And no man has ever apologised for explaining, wrongly, things that I know and they don’t.”

Since then, that essay has become common vernacular in feminist circles and beyond, as the term “mansplaining” caught on and spread like wildfire. It was a word we needed, for a thing we knew was happening, but we couldn’t quite put our finger on. For a way to begin addressing how pervasive and infuriating it is.

Men Explain Things To Me is more than that, though. The essays look at rape culture, at women’s lives, at literature, at writing and being a writer.

It’s a book about distress. I have read my fair share of feminist texts, especially lately, but Solnit’s recounting of the statistics around violence against women is chilling.

“A woman is beaten every nine seconds in this country. Just to be clear: not minutes, but nine seconds. It’s the number one cause of injury to American women.

Spouses are also the leading cause of death for pregnant women in the United States.”

That same essay contains retellings of brutal gang rapes. Of the kidnapping and silencing of women in countries the world over. Of the myriad ways in which we are shouted down, beaten, and killed. Of the myriad ways in which our agency is taken, from the more minor offence of having your own book explained to you, to being subjected to domestic violence, to murder.

“Some women get erased a little at a time, some all at once… The ability to tell your own story, in words or images, is already a victory, already a revolt.”

Solnit has a love affair with Virginia Woolf, something I share. She begins a chapter dedicated to the feminist writer with that woman’s own words: “The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be, I think” – Virginia Woolf, in her journal, January 18, 1915.

But Solnit does not take this for despair, but for hope. She explores our human difficulty with uncertainty, how we try to know the future before it occurs, how we attempt to control with planning. As an anxious person, I related to this on a cellular level. It was also interesting to read a different and clearly extremely well-formed and informed discussion about the place of writing in this process, and the value that writing can have far beyond our view. She recounts a discussion she had with Susan Sontag.

“I had just begun trying to make the case for hope in writing, and I argued that you don’t know if your actions are futile; that you don’t have a memory of the future; that the future is indeed dark, which is the best thing it could be; and that, in the end, we always act in the dark. The effects of your actions may unfold in ways you cannot forsee or even imagine. They may unfold long after your death. That is when the words of so many writers often resonate most.”

I found this very reassuring. Perhaps because I’m anxious person, perhaps because I’m an insecure writer who dares hope that my words may have value, may continue to have value after I’m gone.

Solnit addresses the feminist movement, and the conflicting viewpoints that we have either achieved nothing, or we have already achieved everything. I find this interesting because I know a few people who think both of these things and don’t seem to see them as conflicting. Feminism is useless, and women are already liberated. You can go to work and have a baby. What more do you want?

“Feminism is an endeavor to change something very old, widespread, and deeply rooted in many, perhaps most, cultures around the world, innumerable institutions, and most households on Earth—and in our minds, where it all begins and ends. That so much change has been made in four or five decades is amazing; that everything is not permanently, definitively, irrevocably changed is not a sign of failure. A woman goes walking down a thousand-mile road. Twenty minutes after she steps forth, they proclaim that she still has nine hundred ninety-nine miles to go and will never get anywhere.”

There is so far to go. There is so far to go. This is a constant refrain in my head. When I read the rape statistics, when I see rape jokes being made on social media, when I watch over my shoulder when I’m walking down the street. When I think about the trauma that I and so many of my friends have suffered.

There is nine hundred ninety-nine miles to go, and it’s all in the dark.

But that does not mean we should not have hope. Because not only are we already on the road – we are not walking it alone. Reading books like Solnit’s reminds me of that fact. More and more people are understanding the impact of the epidemic of violence against women. More and more people are recognising the nuances, the levels of violence that take place, the ways in which we can start to address them. More and more are refusing to be silenced.

We may be staring into the dark. But we have gone twenty minutes, and we will go twenty more.