Unless you’ve been hiding under a rock, you’ve heard about what Nobel prize-winner Tim Hunt said about women in science. I have a few things to say in response, and it got me thinking about women in other industries – especially tech and writing.

According to The Guardian, the Nobel winner said ‘Scientists should work in gender-segregated labs’ and that ‘the trouble with “girls” is that they cause men to fall in love with them and cry when criticised.’

Let me tell you about my trouble with girls … three things happen when they are in the lab … You fall in love with them, they fall in love with you and when you criticise them, they cry

– Tim Hunt, speaking at the World Conference of Science Journalists in Seoul, South Korea.

What a load of absolute bollocks.

The Royal Society has responded by saying it “blieves that in order to achieve everything that it can, science needs to make the best use of the research capabilities of the entire population.”

Too many talented individuals do not fulfil their scientific potential because of issues such as gender and the Society is committed to helping to put this right.

The Gaurdian article also says that “the number of women in science, technology or engineering (Stem) has remained stubbornly low. Only 13% of people working in Stem occupations are women, according to Wise, which campaign about this issue. The gap is also stark in academia, where 84% of full-time professors working in science, engineering and technology are men.”

Of course, Hunt’s words have been the centre of a storm of discussion online about women in many industries, not just science.

The hilarious but also bitingly true #distractinglysexy hashtag was born, with women scientists sharing pictures of themselves at work looking like – oh, women scientists at work! What a surprise.

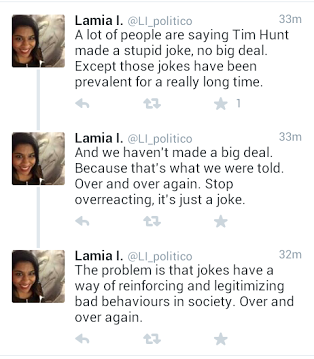

Lamia Imam made some great points.

As far as I know, Hunt has apologised, but stands by his comments. Which isn’t actually an apology, in my book. Why bother saying sorry at all if you believe in what you’ve said? Lamia is right. “Jokes” are a big deal. They are an insidious way and socially acceptable way or reinforcing shitty ideologies. And we don’t have to stay silent about it.

(If I may make an aside for a second – GiggleTV is a perfect example of this, and so are the comments on my latest blog about it).

I was talking to a friend of mine about Hunt, and we got onto the subject of women in tech. My friend, who is a programmer, reacted strongly to the idea that *his section* of IT would be sexist. “Tech is hugely segmented, though!” he said. “I know that people talk about sexism in the tech industry but in my area I’ve never experienced it. So I can’t do anything about it.” (This is paraphrasing a long conversation).

I told him that was a ridiculous thing to believe and he went out for a walk.

When he came back he said: “I was wrong to say that, and I’m sorry. Can we talk more about this.”

(This was pretty exhilarating for me. I gotta be honest, I argue a lot about sexism and that response is rarer than a unicorn’s butt).

So I said to him: “What you did was say that, because you hadn’t personally experienced or witnessed it, it’s not your responsibility. It is your responsibility. The fact that tech is segmented into programmers and web designers and project managers etcetera etcetera makes no difference. The problem is everywhere. You work in this industry. That means you can work for it to be better.”

He wanted to know how.

In 2014, Google reported that 7 out of every 10 of its then 48,600 employees were men. The number was even higher among its engineers and managers, and only 3 of the company’s 36 top executives and managers were women. Google’s disclosures led other major tech companies to follow suit. Apple (98,000 employees) and Twitter (3,300 employees), for instance, reported similar overall percentages: about 70 percent men and 30 percent women. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, the companies also reported that employees were overwhelmingly white.)

I spoke to my friend Tanya Gray about the major issues facing women in tech – what are the barriers to getting in, and what are the barriers to staying there?

“Teenagers I’ve spoken to often say that they didn’t realise there is more to tech than just computers, that it is about the problems we solve, not so much about the technology itself,” says Tanya.

According to the Women in Tech article above, it’s the “boys-only” culture that remains the big obstacle, and it’s at all all levels within the sector. A Catalyst report showed than only 18% of women graduating with MBAs get roles at tech companies, compared with 24% of men. About half the women end up leaving the industry.

“Tech companies can be very “blokey” environments” says Tanya. “It’s all the near-invisible things which add up over time. Being asked to present because they need female representation. Cricket being played on the workplace TVs while being laughed at for your interest in crafts. Hearing the guys talk about their “conquests” on the weekend.”

There seems to be a common misconception that this is a problem that we don’t face in New Zealand, that it’s something “other countries” have to deal with and that it’s not nearly that bad here. The first thing any company can do is acknowledge that there is a problem, and that they may be a part of the problem even if they don’t realise it.

I also told him long list of things he could do more of. Know when to speak up (ie if one of his colleagues is being sexist, or online), and when to be silent (ie when women are having a conversation and a man’s voice isn’t needed). If he ever has his own business, ensure it’s equal opportunity and has inclusive policy. Contribute to inclusive workplace culture.

By the end of the conversation, he went from “I don’t see this in my particular field so I am powerless,” to “I can see there is a problem in the industry as a whole and there are things I, personally, already do and can do to combat it.”

The idea of segmented industries made me think about writing. Our profession is also segmented – journalists, feature writers, romance writers, sci-fi writers, biographers, fantasy novelists, poets.

And, again, women are hugely underrepresented.

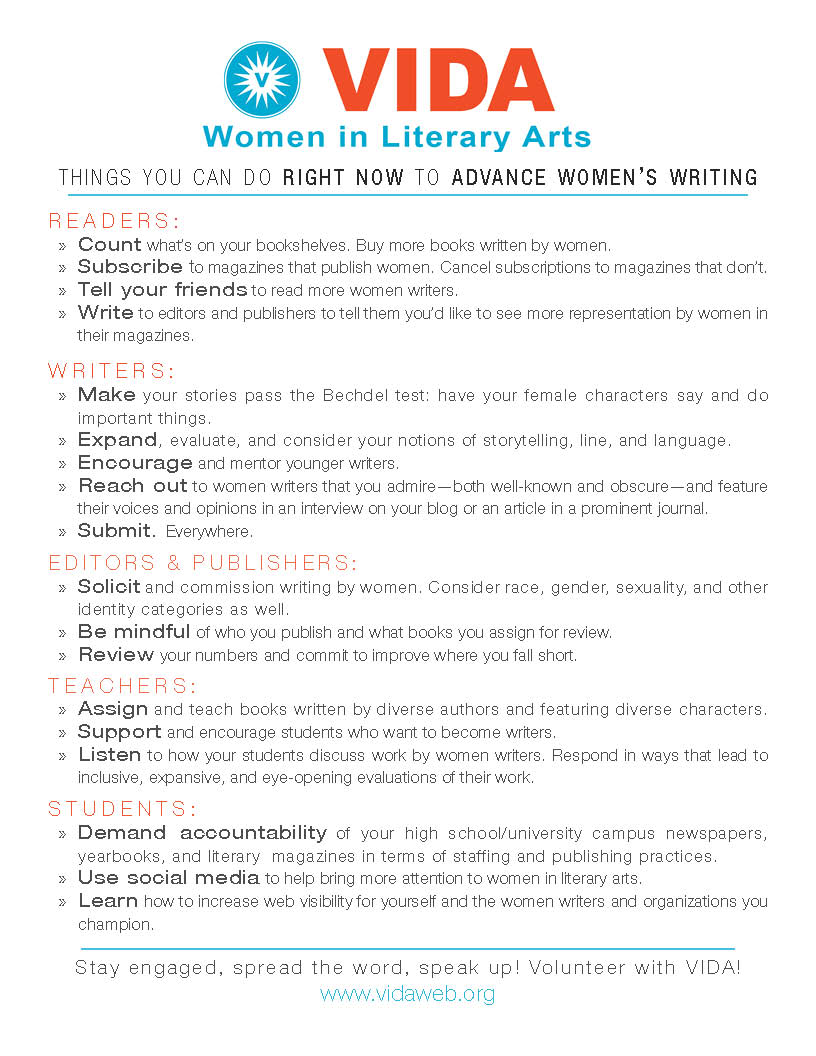

Vida, organisation which looks to further transparency around gender inequality in contemporary literary arts, researchs and publishes valuable statistics on women writers.

The VIDA Count looks at gender balance in “ journals, publications, and press outlets by which the literary community defines and rewards its most valued arts workers, the “feeders” for grants, teaching positions, residencies, fellowships, further publication, and ultimately, propagation of artists’ work within the literary community.”

Here’s some of the 2014 findings.

“This year’s tallies show negative change for women on all counts. In 2013, women represented 51 percent of the pie, a milestone we celebrated. However, this year’s counts point to a sharp decline, an 11 percentage point slide to just 40 percent female and 60 percent male overall.

Overall, we haven’t seen significant positive change at The Times Literary Supplement over five years of our counting. The share of the pie for women has remained at a consistent 27 percent for four years. In 2014, we saw a slight bump to 28 percent, which means that women continue to share less than one third of the pie.

For authors reviewed, the gender gap is still wide at The Nation and hasn’t shown much change over the last four years. Though the percentage of female authors reviewed showed a 4 percentage point increase over last year, increasing from 16 percent to 20 percent, the share of the pie remains dismally small. The pie has remained fairly consistent, increasing by only 1 percentage point from 2011’s 19 percent female. In 2014, the overall share of the pie for women was 29 percent, which was a slight increase from last year, breaking a consistent three-year streak at 27 percent.

A Public Space published more male writers in total, with work by men covering 57 percent of their fiction pages.”

So, why? We know women write. We know they’re good at it. Why aren’t they getting published

Guardian books editor Claire Armitstead said in 2010: “We always try to keep an even balance but many more men offer themselves to review books than women, so we have to go out and find them. My own feeling is that there is an issue of confidence among women writers.”

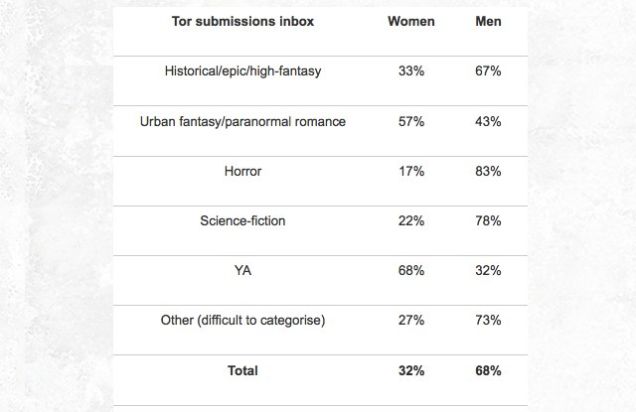

This theory is backed up by Julie Chrisp of TOR UK publishing. TOR monitored their open submissions box for a month. Out of 503 submissions, 32% were from female writers.

It’s not really surprising that women authors don’t back themselves as much as men. This happens across industries.

This article in The Atlantic looked at a study by the Cornell psychologist David Dunning and the Washington State University psychologist Joyce Ehrlinger homed in on the relationship between female confidence and competence.

“Dunning and Ehrlinger wanted to focus specifically on women, and the impact of women’s preconceived notions about their own ability on their confidence. They gave male and female college students a quiz on scientific reasoning. Before the quiz, the students rated their own scientific skills. “We wanted to see whether your general perception of Am I good in science? shapes your impression of something that should be separate: Did I get this question right?,” Ehrlinger said. The women rated themselves more negatively than the men did on scientific ability: on a scale of 1 to 10, the women gave themselves a 6.5 on average, and the men gave themselves a 7.6. When it came to assessing how well they answered the questions, the women thought they got 5.8 out of 10 questions right; men, 7.1. And how did they actually perform? Their average was almost the same—women got 7.5 out of 10 right and men 7.9.

To show the real-world impact of self-perception, the students were then invited—having no knowledge of how they’d performed—to participate in a science competition for prizes. The women were much more likely to turn down the opportunity: only 49 percent of them signed up for the competition, compared with 71 percent of the men. “That was a proxy for whether women might seek out certain opportunities,” Ehrlinger told us. “Because they are less confident in general in their abilities, that led them not to want to pursue future opportunities.”

It looks like the ‘confidence gap’ is real. It’s contributing to men like Hunt thinking it’s ok to say that women are distracting and weak. It’s contributing to underrepresentation of women in a huge variety of vital fields where our voices and skills would be so valuable.

So – what can you do?

That’s for writers – but I think it can be easily applied across the board.

That’s for writers – but I think it can be easily applied across the board.

It’s a start, anyway.

– WH