This blog brought to you by a weird mashup in my head of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, feminist thought, history vs present, and writing

I’ve just finished reading A Room of One’s Own. To say I was enthralled would be an understatement. To say it’s a defining feminist text is way too academic and would fail to accurately describe the breathless excitement that forced me to pretty much copy out every page. (Seriously. So many notes. How can someone be so ridiculously quotable?)

Virginia Woolf wrote A Room of One’s Own in 1929, based on a series of lectures she gave on women and fiction. In a gripping, exaggerated but largely nonfiction narrative, she leads us through a history of men’s opposition to women’s emancipation, particularly in relation to women writers.

‘Why was there no woman Shakespeare?’ she asks. Simple. There couldn’t have been. To prove the point, she creates a fictional ‘Shakespeare’s sister.’ As talented a writer as her brother, the young lady declares herself as a writer and is laughed out of the house. She escapes to the city, as he did, to follow her dream, and is subsequently taken advantage of by a string of men, as there is no way for her to support herself, and no one will give her writing any credit. She ends up pregnant and alone, and is buried in an unmarked grave beside a railroad.

This is evocative, poignant – and all too real.

The most jarring moments in A Room of One’s Own are not those that are so emotional, however. It’s those where Virginia Woolf, in 1929, predicts a future of gender equality.

“… in a hundred years, women will have ceased to be the protected sex. Logically they will take part in all the activities an exertions that were once denied them.”

Well, it’s been almost a hundred years, Virginia, and I’m really sorry to report that… things are not going so great.

Feminism is still a dirty word. Women and men are afraid to call themselves feminists because of the stereotypes and false negative connotations associated with that identity. I call bullshit on this.

In addition to the fascinating study of the development of women as writers in a historical context, Virginia looks at the current situation (current being 1929), which again, is pretty much the same as now.

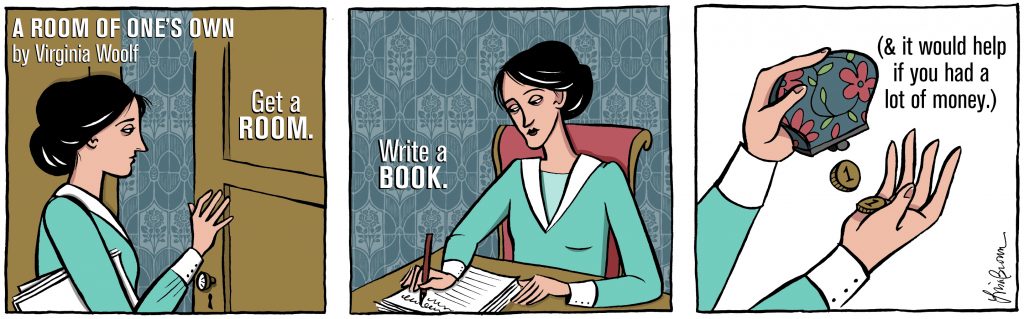

She has one thesis, which is in the title:

Great read. Pepped me right up for the afternoon.

Thanks so much. You had me at a room of her own.

Pingback: The Seventy-Seventh Down Under Feminists Carnival | Zero at the Bone

Pingback: What to do when you can’t do it | Writehanded