‘A female writer cannot afford to feel her life too clearly. If she does, she will write in a rage when she should write calmly.’

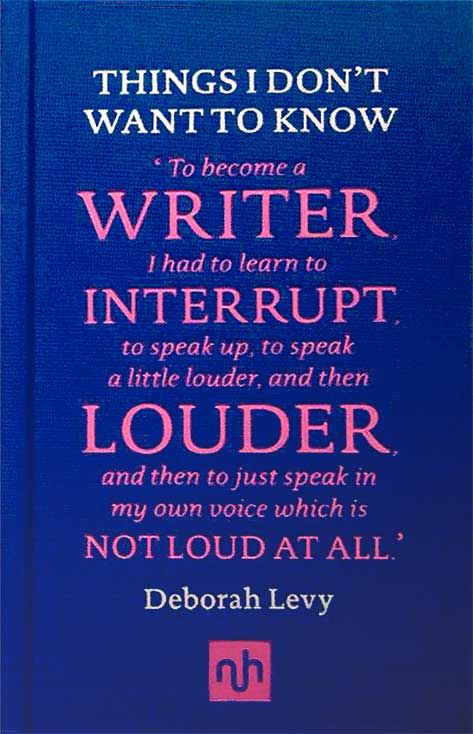

I read Deborah Levy’s Things I Don’t Want to Know all-at-once. I did not twitch. I did not get up and get a cup of tea. I think I forgot to breathe. It was most unusual.

When I closed it, I thought to myself; “That is a book that changed my life.”

Every book changes your life, if you read it right. Some will do it properly.

I have a lot of rage. I often write with it. That is ok. That can be a good thing, I think, especially when silencing tactics such as the words “angry feminist” are commonplace. It is the editing that must be done calmly.

Things I don’t Want to Know is a book about writing. It is a book about being a woman who writes. It is a book about being a woman in the world.

It is thoughtful, and cute, and terrifying, and abrupt at surprising moments. It caused my throat to convulse. It caused a mild rushing in my ears. It made me think about the things that happen in your childhood that become your relationships, your language, your politics – that become you as a writer.

I am a fairly recent feminist. I have read many things, in this short time, about feminism. I have read many things written by feminists.

This thing, which is not solely feminist or autobiographical and certainly wouldn’t call itself a manifesto, though it does call itself a response (a title I think highly unnecessary, as it stands quite alone) – this thing is the closest thing I have found to a reason.

“Speaking up is not about speaking louder, it is about feeling entitled to voice a wish.”

This is a book about finding your voice, in a patriarchal world where we are socialised to not express our wishes, and if we do, we must do so quietly.

When I was in the bookshop buying this book I saw yet another ‘laughable take’ on the trope of the loud, angry voices of men. Except it wasn’t laughable, because the trope is true and here it was. Men are not told to be quiet, or write without rage. Men are given megaphones.

Where was my channel? Does anyone care that I am angry? Me, as a woman? Me, as a writer? Me, as my mother’s daughter?

On the first page of Things I Don’t Want to Know Deborah Levy stands on a moving escalator and weeps. I am a public weeper too. Neither of us really understood why.

“Like everything that involves love, our children made us happy beyond measure – and unhappy too – but never as miserable as the twenty-first century made us feel. It required us to be passive but ambitious, maternal but erotically energetic, self-sacrificing but fulfilled – we were to be Strong Modern Women while being subjected to all kinds of humiliation, both economic and domestic. If we felt guilty about everything most of the time, we were not sure what it was we had actually done wrong.”

I’ve heard this before but I’ve never heard it in this way. A way that felt visceral, a way that left me stinging and raw. As did this next piece, speaking of the various women in her life, and herself.

“They are on the run from the lies concealed in the language of politics, from myths about our character and our purpose in life. We were on the run from our desires too probably, whatever they were.

The way we laugh. At our own desires. The way we mock ourselves. Before anyone else can. The way we are wired to kill. Ourselves.”

Gosh, ok, remember that breathing thing? Do it now.

Among the almost non-stop knockouts are some profoundly sweet moments. On a Saturday when 15-year-old Deborah was attempting to do enough cleaning to be allowed to leave the house to go and write on paper napkins at the local diner, an unlidded honey pot falls into the washing machine. Attracted by the scent, a swarm of bees enters the open window. Deborah, increasingly alarmed and desperate to get to the diner, attempts to smoke them out with joss sticks. Drugged, they fall into a stupor and submerge themselves in the honey. She spends hours scooping stoned bees and sticky honey from the washing machine. Her hands are stung many times. She is unable to write.

“A female writer cannot afford to fee her life too clearly. If she does, she will write in a rage when she should write calmly.”

These words were inspired by Virginia Woolf, who went on to say; “She will write foolishly when she should write wisely. She will write of herself when she should write of her characters. She is at war with her lot.” (A Room Of One’s Own, 1929).

I am at war with my lot. I write with rage often, and I write of myself. I don’t think is unwise, for now. It is perhaps my current purpose.

Calmness is an attribute – no, a luxury – that many women cannot afford. Calmness does not always equate to wisdom. Crying on escalators is not calm. But it is powerful.

It was not calmness which drove me to finish this book, then to sit cross legged in my tangled bed covers into the small hours of the morning, writing all of this in a notebook with a golden eyed cat on the front, using a pen made of purple glitter that rubs off my palms and scatters through the sheets.

“It’s exhausting to learn how to become a subject, it’s hard enough learning how to become a writer.”

No, I am not calm. I am in wonderment. I am exhausted. I am learning. I am, in fact, enraged. And I know what to do about it.

Today I saw a book that proclaimed, glorified, and manifested the opinions of angry old men.

Today I bought a book called Things I Don’t Want To Know.

Pingback: Some quick recommendations | Writehanded